Chicago’s Art Institute Has Been Captured — And the Impressionists Are Hostages

Come for the masterpieces, stay for the struggle session

Gustave Caillebotte (1848–1894) was the Impressionist your blue-haired art teacher skipped because his life blew up the whole "selfish–white–guy–patron–of–the–arts" narrative. He wasn’t just a wealthy Frenchman. Caillebotte was, in hindsight, one of the top Impressionists, with 10 times the talent of the sum of the intersectional wannabees now hanging beside him at the Art Institute of Chicago, where curators have decided that identity is the new brushwork.

Back to Caillebotte, whose path into art was anything but ordinary. He trained as an engineer, dabbled in law, then decided to paint. Yet Caillebotte didn't end up as just another dilettante with good tailoring and expensive brushes. Caillebotte could paint. I mean, really paint. The Floor Scrapers, with its sweaty realism, and Paris Street; Rainy Day, with its cinematic geometry, proved he could hang with Monet and Renoir in any gallery — literally.

But Caillebotte, to channel my inner Whitman, contained multitudes — yachtsman, gardener, and, above all, benefactor. He spent as much time bankrolling the Impressionist cause as making his own work. But you won’t find a single description of that next to his body of work. He bought his contemporaries' paintings (often at higher prices than the market) when no one else would, funded their exhibitions, and kept them solvent enough to keep up their craft. In Yiddish, we’d call that a mensch — someone who quietly does the right thing without needing to turn it into performance art.

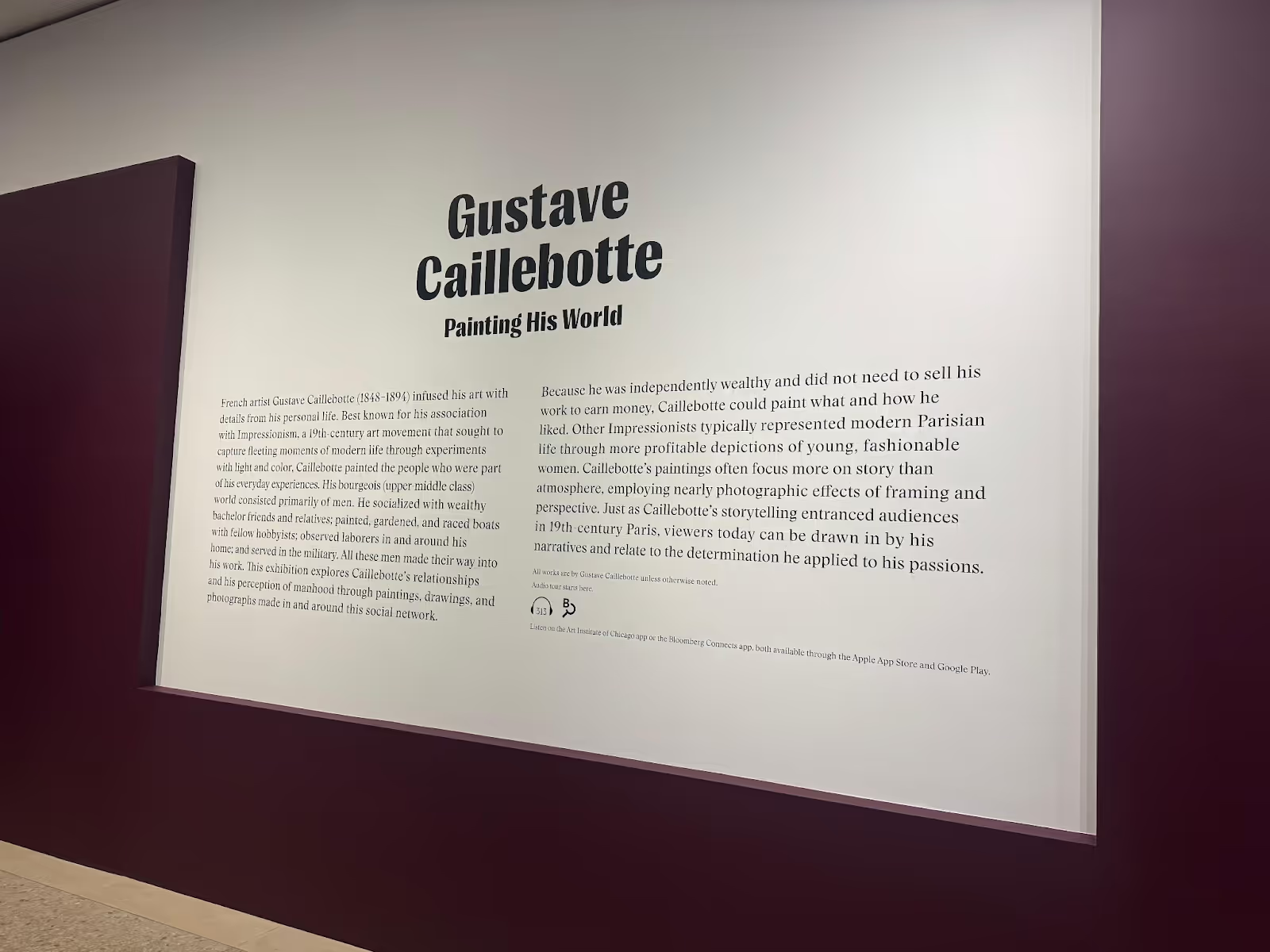

That’s the real history. But walk into Gustave Caillebotte: Painting His World at the Art Institute, and the first wall makes it clear this show isn’t about Caillebotte the benefactor or the prodigious talent. It’s about Caillebotte as patriarchy — a walking case study in cisnormativity and white privilege.

The curators congratulate themselves for unearthing his “bourgeois social network” and “independently wealthy bachelor friends [undoubtedly white friends].” They repeat, like a catechism, that he “did not need to sell his work” — as if being born a certain way is a moral failing. No mention that this same man funded Monet’s paint, Renoir’s brushes, and Pissarro’s canvasses. Without his checkbook, half the generation might have been back to painting someone’s aunt for rent money. But here, it’s reduced to “boat racing” and “garden parties” — a résumé of leisure pasted over the fact that he was both the financial engine and a front-line general in the Impressionist rebellion.

The Floor Scrapers label reads like minutes from a life-drawing class: "Studying the male body," "live models," "emphasis on form." No mention that in 1875, three shirtless men scraping a Paris floor was practically pornographic by Salon standards — a direct insult to the establishment, giving working men the heroic treatment usually reserved for gods or generals.

House Painters gets even less respect. The big insight? "Different hats." On the canvas: tradesmen scaling ladders, mixing pigment, lettering shop signs with the same precision Caillebotte used in Paris Street; Rainy Day. He wasn't "likely identifying" with them in some cutesy cross-class moment; he was putting them on the same cultural footing as himself.

The "Working Men" wall is where the woke scalpel slips: "wealthy idleness," "cross-class affinities," "art reflects his privilege." Yes, Caillebotte didn't need to work, which is precisely why it matters that he used his skill painting people the market didn't reward. If "reflects his privilege" means "used freedom to elevate laborers in oil at full scale," then we should pray for more privilege like it.

Portrait of Jean Daurelle is called "respectful," as if respect were garnish instead of the whole meal. Top hat, frock coat, posture straight as a yardstick — Caillebotte fixed him into history with the gravity of a banker or statesman.

Young Man at His Window is reduced to "boredom or restlessness." It's not boredom — it's a meditation on looking, on the threshold between private safety and public spectacle. And Young Man Playing Piano is waved off as "a leisure activity for bourgeois women," missing that Martial, his youngest brother, is locked in the grind of mastery. Whether you're scraping floors or playing Chopin, work is work.

In a Café, the label leans on Huysum's sneer that such men "do not have great thoughts." What actually appears there is a democratic stage of modern life. The Soldier portrait is framed as missing "masculine activities of war," ignoring that Caillebotte humanizes instead of mythologizes.

Men at Home gets the gender-studies boilerplate about "male social circles" and "domestic spaces associated with women," skipping the fact that his interiors are psychological studies in intimacy and control. Portrait of Paul Hugot is boiled down to "bourgeois silk top hat," ignoring that Hugot was both patron and subject in Caillebotte's commentary on class.

By Paris on the Street and From the Balcony, the wall text is locked into "limited to the wealthy" and "ownership over the city." These balcony paintings aren't about landlord privilege — they're about perspective, geometry, and compositional grammar, unlike anything else in Impressionism.

Which makes this all a poor reflection on Gloria Groom, Scott Allan, and Paul Perrin, who curated the exhibit. They know the material cold — PhDs, decades in the field — which is why it's galling that the wall text reads like it was subcontracted to raving maniacs who skimmed Das Kapital, minored in Art Outrage, and obsessively follow Greta for inspiration.

Instead of telling you about Caillebotte the patron, the engineer-painter, the radical realist, they green-lit prose about "cross-class affinities" and "bourgeois social networks" like we're trapped in a freshman grievance-studies seminar.

The irony? You’re underwriting it, along with your investment manager. Raymond James — the lead sponsor, the same people managing your retirement account — should be appalled that their name is stapled to this circus. Add in the corporate donors and private collectors who made the whole thing possible, and you’ve got an entire class of patrons bankrolling the ideological rewrite of the works they supposedly cherish — funding a revolution, then acting surprised when their own property is set on fire or “redistributed” at gunpoint on Chicago’s streets.

In the old days, you could counter the wall text with a docent — volunteer encyclopedias who could quote provenance, technique, and gossip without a binder. They're gone, purged in 2021 under "equity," replaced by paid "visitor engagement" staff: black-clad, mask-wearing hall monitors whose job is not to expand your understanding but to keep you inside the chalk lines of the official narrative and make you think about your power and privilege. As your trusty correspondent was at the exhibit just before closing time, the irony of the docents shouting out the countdown until they could punch the clock did not go unnoticed.

That's the most insidious part. The Art Institute doesn't just want you to see Caillebotte through their lens — it wants to make sure you can't see him through any other. You're in their sealed world of intersectionality and oppression, where "privilege" is the primary pigment and every canvas is repainted to match the ideological swatches of the season.

On the one hand, there’s no single “correct” way to interpret art. If race- and gender-obsessed Marxists want to deconstruct it to fit their worldview, fine — I’ll tip my hat, not because I agree, but because it adds to the mix. On the other hand, when they seize the narrative entirely, wall off dissenting views, and — just as they shout down opposition whenever someone disagrees — show a readiness to use violent means to purge whiteness and Jews from their rainbow-curated corner of the world, it’s time someone raised the flag.

Play this out far enough and the destination is clear: the art becomes irrelevant, the artist a prop. There is no "art," only "institute," and the institute's function is not to inspire or provoke, but to dictate not just what you think, but, you’ve heard this already, “how you think”.

Here's the real kicker. It's not just Raymond James and the museum’s most prominent patrons paying for this. It's the everyday Art Institute members like me who want to come in from the cold world to be inspired by creative genius, only to be told that what our soul tells us must be inspired by the divine, is only a byproduct of whiteness.

We may think we’re funding art, but we’re funding the very curators and freshly minted DEI hires chosen for their skin color, gender identity, and ideology rather than expertise and aesthetic subtlety. These people despise the very modern Gettys and Caillebottes, who are generous enough to give of their love, time, and talent. They hate the very people paying their salaries.

I’d go so far as to say they want us dead unless we comply. In the spirit of Caillebotte's own Paris (at least a century earlier), I’m sure they'd happily march the donors to the guillotine in the name of equity. All they curate is the very violence they want to bring to launch the revolution. And yet we're all paying for the privilege of art re-education and, well, the Marxist deconstruction – no destruction – of art itself, Foucault be damned.

I don't know about you, but I've had enough. It’s time to take the Art Institute back. But that job will have to fall to someone better than me. I’m not your Blutarsky here. These days, I'm spending more time at Wrigley channeling my inner Bill Murray than being cultural, savoring the art of baseball and the best Cubs offense in decades.

I’ve already lost 20 IQ points to my Old Style intake, and raw brainpower — apparently a symptom of white privilege, I hear — is critical if you’re going to go to war with captured institutions and win, Chris Rufo–style. Besides, my only performative outrage lately is reserved for the Ricketts, who yanked my favorite ballpark beer off draft in the upper deck.

So it’s on you — the patrons, the donors, the lenders — to take the Art Institute back from the blue-haired commissars who’ve hijacked it. Do it for Caillebotte. Do it for art that speaks in brushstrokes, not in hashtags. And for God’s sake, do it before every canvas in the building is repainted in the colors of the revolution.

J.D. Busch recently paid $110 to join the Art Institute of Chicago. In hindsight, they probably should’ve turned him away at the door — because he plans to get his money’s worth as the Chicago Contrarian’s newly self-appointed, unpaid, and thoroughly unhousebroken art critic.